Leopold Tyrmand (centre) enjoying time with Jazz musicians in the late 1950s

‘Is there a conflict between me and the rulers of this country? Yes there is. A difference of opinions. I think differently. We differ in our views on the constitution and architecture, on industry and sport, on personal freedoms and education.’

Leopold Tyrmand, Diary 1954

After all us Poles don’t like training, every Pole knows that, as does every foreign coach who works in this country. Here we just want to play. If there are two goals we need to go and kick the ball at them for 20 minutes at a high tempo. Then, and only then, can we lay on the grass with our tongues hanging out. Training just doesn’t float our boat.’

Leopold Tyrmand, Przekrój, May 1948

In the gloom of post Second World War Poland, as the country tried to raise itself from the rubble wreaked by Nazi occupation and the Red Army imposed a new order from the East, many people aimed to retain some semblance of the Poland which had been torn apart in the late summer of 1939. Leopold Tyrmand, who returned to Warsaw in April 1946 after an eventful war abroad, was one of those people. Tyrmand was from a middle class family of assimilated Polish Jews who were wealthy enough to send the young man to study Architecture at the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris for a year in 1938. Tyrmand’s father was murdered at the Majdanek death camp in Lublin, his mother survived the war and subsequently emigrated to Israel.

On returning to Poland the educated Leopold was faced with the same complicated choices as the majority of the Polish intelligentsia. Although some Poles continued to fight the imposition of Communist rule and a select few accepted the new regime with open arms, the great majority, while not committed Communists, realised they needed to make some form of accommodation with the new rulers. In the immediate post-war years however Polish Communists couldn’t fully impose totalitarianism on Polish society due to an unstable geopolitical situation and the sheer lack of domestic support for a Moscow backed regime. Between 1945 and 1949 there thus existed an element of cultural space for non-conformity – something that meant the rebirth of theatres, cabaret shows, and jazz clubs – culture that was gobbled up by a Polish society which had little chance to express itself under Nazi occupation.

Tyrmand thrived in this cultural climate, he was a free-thinker, an aesthete and above all an individualist – but someone who realised that he had to compromise with the new post-war reality in order to survive. Times were however to get tougher, in 1949 Polish Communists felt strong enough to impose their visions on Polish society and cultural conformity was introduced, something which remained in place until the mid-1950s when a ‘thaw’ occurred in the aftermath of the death of Stalin.

Tyrmand’s fortunes ebbed and flowed in the first post-war decade. Initially he wrote feuilletons for the liberal elitist Marxist cultural journal Przekrój and, after being thrown out of the magazine in 1950, he wrote for the liberal Catholic weekly Tygodnik Powszechny – the only independent newspaper in the Communist Eastern Bloc. After the publication was closed down by Polish Stalinists in 1953 for its independent stance Tyrmand experienced considerable difficulties from the authorities. The release of his noir crime thriller Zły (Bad) in 1955 saw Tyrmand come out of the wilderness to experience fame in Communist Poland. However he experienced further problems by the end of the 1950s as Communism tightened its grip on Polish society once more – in 1965 Tyrmand was allowed to emigrate to the United States.

Tyrmand is known in Poland for being a staunch anti-communist but above all for being a non-conformist hipster at a time when this was frowned upon, and even seen as a sign of ‘enemy’ activity. Tyrmand was the symbol of the bikiniarze, the ‘bikini-boys’ – a movement which flew in the face of staid Stalinist conventions. The Bikini-boys dressed differently, basing themselves on fashion styles from the West and danced to jazz music which was officially outlawed from 1949 onwards. Tyrmand loved jazz, wore the ‘duck-tail’ hair-do of the bikini-boys and, famously, bright socks – all things which were seen as an act of protest against Communist cultural mores. As renowned Polish song-writer Agniesza Osiecka stated:

“The whole world could wear whatever socks it wanted, but the red or striped socks of Tyrmand were not only socks. They were a challenge and an appeal, they were a charter of human rights. These socks spoke for the right to be different, or even the right to be silly. They declared: This is me, this is me. I don’t want to be one of many; it’s enough to be one of two.'”

Tyrmand, by word and action fought tirelessly to create a level of autonomy for the individual in a Polish cultural world dominated by collectivist norms. He did so by applauding the joys of life: music, art, sex and as we will see, sport.

Tyrmand, Przekrój and sport

After arriving back in Warsaw Tyrmand was lucky enough to get a chance to write for the exclusive cultural magazine Przekrój – a magazine in which the Crème de la crème of the Polish cultural world appeared. Polish literary greats such as Zofia Nałkowska, Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz and Konstanty Gałczyński all regularly wrote for the magazine, so Tyrmand was among elite company. The magazine had been set up in 1945 by liberal Marxists who aimed to appease Polish urban intellectuals and to be a cultural bridge between the worlds of Western capitalism and Eastern Communism . As Tyrmand himself explained: ‘Przekrój fought in the name of art, of a certain kind of artistic creation in the fields of theatre, film and fashion….It wanted to bring Picasso, Steinberg and André François to Novosibirsk…’

Although Tyrmand wrote articles about a variety of issues for Przekrój he became known for his weekly feuilletons about sport. This was a rather difficult task as the readers of the magazine were not known lovers of sport – Tyrmand thus often had to lead his readers by the hand while explaining the ins and outs of the sporting world. One regular device of Tyrmand was for example the explaining of sports culture to Agnieszka – a girl he was seeing at the time – his sermons are somewhat patronising and sexist but serve an educative purpose. He once for instance explained to Agnieszka that sports-fans were not to take pity on sportsmen during events as in sport one must accept that ‘the best man wins.’

Over three years Tyrmand wrote about a whole gamut of sports for Przekrój, including boxing, tennis, rowing, gymnastics, fencing and others. Several things can be noticed when reading his feuilletons: first and foremost Tyrmand understands the place of sport within the modern world. In one article in May 1948 he calls sport ‘the most modern disease.‘ He goes on to state: ‘In 100 years young people will study about the history of sport in their country.‘ In another article he chides those who see sport as culturally unimportant – explaining that: ‘The psychological state of entire societies are now often dependent on the scoring of a single goal‘ and that: ‘Sport is now a part of life. It is no longer just entertainment, but rather a fragment of the social and national reality. Just like finance, culture, industry, the legal system and transport.’

Secondly Tyrmand was a great populariser of sport. He often focused on characters surrounding sport, showing how their enthusiasm made events so enticing. He talks about gamblers, experts, the Warsaw elites watching tennis events in their fancy clothes – in short Tyrmand is a great observer of human activity. In one article he explains how emotions are the very essence of sport:

‘A wonderful experience for me was viewing a Kraków waiter whose radio broke at the restaurant during a match between Poland and Finland. The waiter immediately rang his wife so she could place the receiver next to his home radio so he could listen to the broadcast. You could see how the match was going by the expressions on his face alone – but he also relayed what was happening to other waiters in the restaurant and the information was passed around joyfully. He stopped serving meals and I had the impression that even if his boss had threatened to fire him, he would have found it difficult to tear himself away from the phone.’

Although Tyrmand applauded positive aspects of fandom he also strongly criticised what he perceived as improper behaviour at sporting events. He was disappointed for instance by tennis fans cheering the British Davis Cup team’s on-court mistakes during their visit to Warsaw in May 1947. In addition in August 1947 Tyrmand castigated fans for their habit of throwing bottles into boxing rings when they didn’t agree with the outcome of contests.

Here Tyrmand also mentions the boisterous actions of fans at football matches – at one match for example between the representatives of the cities of Warsaw and Łódź fans were so angry at the referee that they tried to attack him on the pitch – eventually the referee had to be protected by security guards! In addition during a Poland-Bulgaria match he looked on disapprovingly of fans desire to send on a certain defender who would ‘do a job’ on the other team – i.e. kick them off the park. To Tyrmand these actions brought shame on Poland and gave sport a bad name.

Tyrmand’s articles thus give a fascinating insight into the sporting world of late 1940s Poland – but what did he have to say about football?

Tyrmand and football

Firstly it’s important to state that football was not one of Tyrmand’s favourite sports, something that he explained in a feuilleton in May 1948:

‘Why is it that this sport, and not some other, galvanises the masses, attracts tens of thousands of viewers and gets crowds excited? There are sports that are more educationally and physically valuable than football. There are many sports which are more attractive, interesting and scintillating. A football match must be of a very high technical standard or create an atmosphere of great emotional tension for it to be really enthralling. It turns more easily than other disciplines into an unattractive spectacle. But football is like the woman you love- it has to be that one and there’s nothing that can be done about it.’

Despite this emotional distance to the sport Tyrmand still found the spectacle of football interesting. Tyrmand’s pieces in Przekrój deal with football as a side issue generally – whereas several articles deal directly with the state of football in Poland. As mentioned above Tyrmand did not enjoy the poor behaviour of football fans at matches but at other times he was caught up in the hysteria surrounding games. One such event was the Polish national team’s match against Czechoslovakia in May 1948. Here Tyrmand praised the atmosphere of ‘holy war’ that engulfed the game:

‘From eight o’ clock on Sunday morning people headed towards the stadium in Warsaw. Trains from Poznań, Kraków, Łódź and Silesia and huge lorries dumped tired and yet excited masses onto the streets of Warsaw. These people, laden with supplies, suitcases and food, camped outside the gates of the stadium until it opened. Roads leading to the capital were full of cars festooned with flags, banners and signs. The spirit of holy war hung in the air.’

In addition to describing the excitement around games Tyrmand also touched on the poor organisation of football in late 1940s Poland. One article for instance focuses on the lack of desire of Polish footballers to train properly – and their desperation to just ‘play games.’ Luckily Tyrmand notes that this attitude was slowly dying out. Another piece explains the serious problem of alcoholism in the Polish game: ‘On Sunday they put everything into the match, and after they win they go out on the town. The players then keep on partying all week which obviously means its pretty difficult to win when next Sunday comes around.’ Tyrmand’s solution to this issue? Legalise professionalism – during Communism football was officially an amateur endeavour.

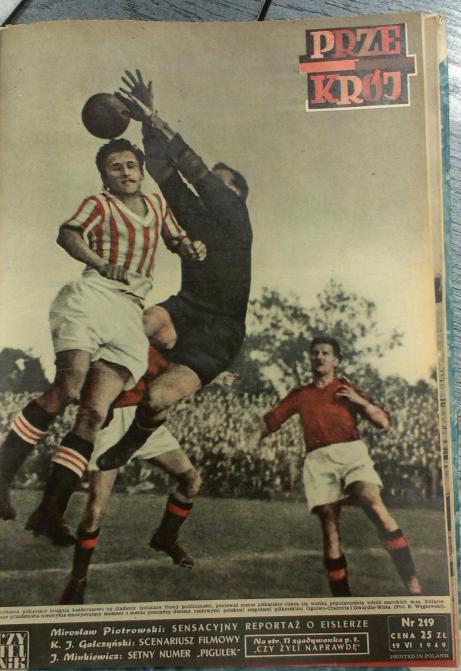

Finally Tyrmand himself attends several matches. His descriptions of matches are given from a very personal perspective as he observes the crowd much more than events on the pitch. They are, like the rest of his feuilletons, lighthearted, humorous accounts, written with the distance of the aesthete that he was. The most important match he attended was a playoff for the 1948 Polish league title between Cracovia and Wisła. The two city rivals had finished the season equal on points – so a one-off match was organised to decide the title – held at the ground of fellow Kraków side Garbarnia.

Cracovia take on Wisła in a derby game in June 1949

Tyrmand goes along to the game with two friends from other cities who are not really big football fans. Tyrmand had a desire to watch the match for the ‘literary nature of the event‘ and the chance to watch two traditional rivals face off against each other. He wasn’t really emotionally involved however as, coming from Warsaw, the result didn’t matter to him. Tyrmand and his friends initally support Wisła but only due to standing in an area where their fans were situated: ‘We behaved like the fans of Wisła, as if we ourselves wanted to finish off the chances that the team couldn’t put away.‘ Cracovia, however, raced into a two goal lead – at which time even the Wisła fans started to cheer on Cracovia (that wouldn’t happen these days!). Eventually Cracovia came out on top to win 3-1 and claim the title. The match seemed to be relatively good-natured though – Tyrmand only noticed one fan who had a strongly adverse reaction to the result:

‘One fan had a dark look on his face and tightened fists as he left the stadium. He kept repeating ‘Cracovia won, Cracovia won.’…However there was no hatred in his voice, only a good amount of bitterness and sadness.’

Epilogue

Tyrmand didn’t stay long at Przekrój, his dislike of the regime showed its face in the spring of 1950. At this time a Soviet boxing side came to fight against the Poles in Warsaw. The referees clearly favoured the Soviet fighters who fought dirtily to achieve victory. The Polish crowd were annoyed and showed it via a barrage of whistles and anti-Soviet chants and slogans. Tyrmand sent in a report to Przekrój stating that the crowd had ‘behaved especially objectively‘. He had expected the censor to cut the phrase out – but this didn’t happen and he was immediately kicked out of the paper and the Polish Journalist association.

In his Diary 1954 Tyrmand railed against every aspect of Polish Stalinism – criticising the lack of political and artistic freedom, the absence of essential items in shops, the poor transport infrastructure of Warsaw but also the sporting failures of the regime:

‘The fall of sport in post-war Poland is a terrible and exceptional phenomenon. Poles have gone from being a nation well respected at the stadiums, pitches, ski-jumps and rings of the world to one that counts very little. We are not taken seriously at all – recently we even lost two football matches in a row to Albania.’

It was indeed a sorry state of affairs. Tyrmand did a good job of catching the zeitgeist of Poland’s sporting world in the immediate post-war period. His texts speak of his great desire – but also what he perceived as a great potential – for normality in Communist Poland – something that touched sport and art in general. Poland’s communist rulers, although at times exhibiting more or less tolerance regarding cultural freedoms, would and could not let this normality fully flourish.

This piece draws on Leopold Tyrmand Diary 1954, Tyrmand Warszawski: Teksty niewydane and Sławomir Koper Skandaliści PRL.

Roger P. Potocki Jr. “‘The life and times of Poland’s Bikini-boys’.” and Norbert Zmijewski ‘Vicissitudes of Political Realism in Poland: Tygodnik Powszechny and Znak.’

and articles from Przekrój magazine